Is anybody's E-Safety curriculum actually working?

It seems everyone's talking about Adolescence and schools banning mobile phones, but is a simple truth being missed: smart phones and social media just aren't safe for children.

Before I start, three apologies.

First, I normally try to make these blog pieces balanced and open ended. My aim is to ask interesting questions and offer new perspectives, not to promote certain viewpoints or preach answers at you. But this week…well, it’s going to get preachy I’m afraid.

And secondly, an apology to Jonathan Haidt for the fact that virtually everything I say is going to be ripped from his brilliant book Anxious Generation. It’s fascinating and terrifying and if you haven’t read it already then I can’t recommend it highly enough.

And thirdly, there is a chance that everything I’m about to say is just old man talk. When I was a teenager, I thought it was hilarious that lots of boring adults seemed convinced that listening to gangsta rap was going to lead me to a life of crime and degradation. It definitely didn’t: I find it stressful when our whole family shares one refillable drink at Nandos. And now here I am - telling anyone that will listen - that smartphones and social media are doing untold damage to our children. I realise it’s possible that I’ve just become one of the boring adults. But what we’re talking about here is the fact that virtually every human being on the planet now spends literally thousands of hours of their lives glued to a device that they carry with them everywhere they go. This is not Snoop Doggy Dogg and some baggy jeans. I really think that maybe this time the sky is actually falling down, and that this is something we should all be panicking about. Even if that makes me sound like an old fart.

Oh, and one more quick thing before I start: I genuinely loved Adolescence as a bit of thought provoking TV. But I was slightly alarmed to discover that our secondary schools are mostly staffed by incompetent bumblers. And then I remembered that IT WAS NOT A DOCUMENTARY. Hope the general public don’t make that mistake eh!

Right, here goes then, for starters, for anyone that’s sceptical that there’s actually a problem out there, we’ve got to look at some graphs…

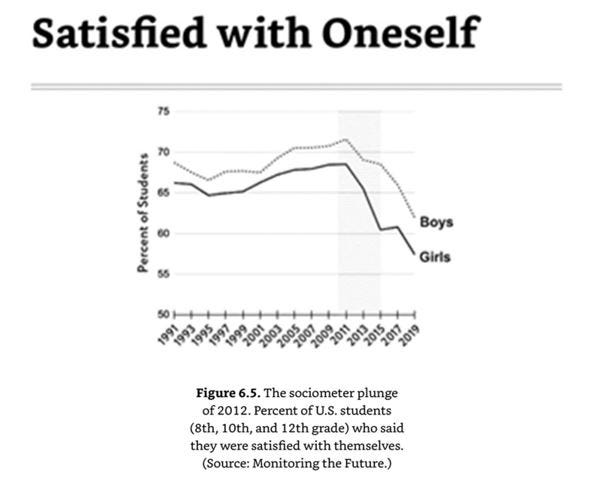

Graph 1, the percentage of 13-18 year olds who say they are satisfied with themselves in America.

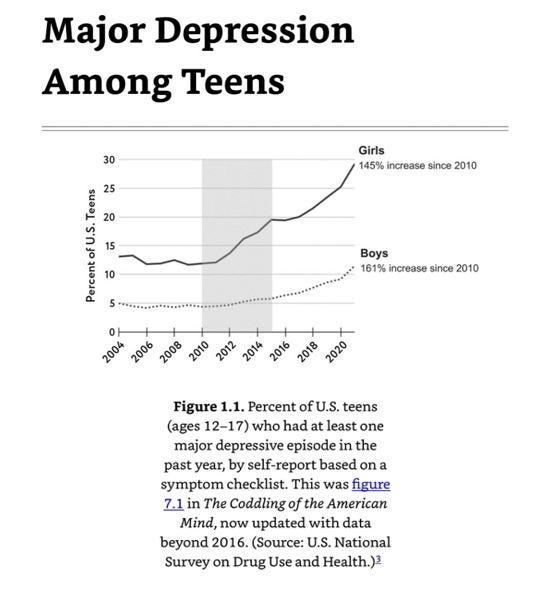

Graph 2, the percentage of American teens who reported having a major depressive episode in the past year.

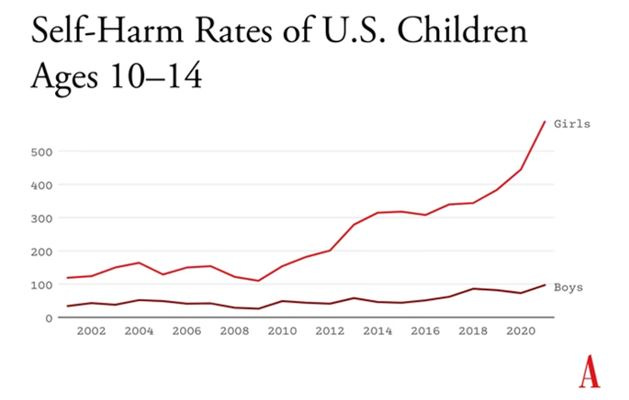

Graph 3, self-harm rates of American children over the last two decades.

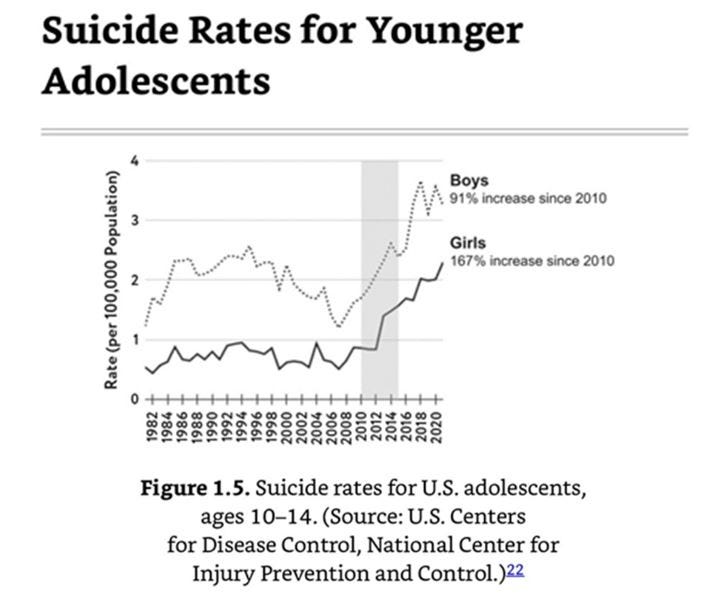

Graph 4, suicide rates for American children between the age of 10-14.

If you look at these graphs, you’ll notice two things:

1) There are scary falls and rises - especially for girls - that should alarm anyone with an interest in the welfare of our children and young people

2) These massive negative trends all start just over a decade ago and then just keep getting worse

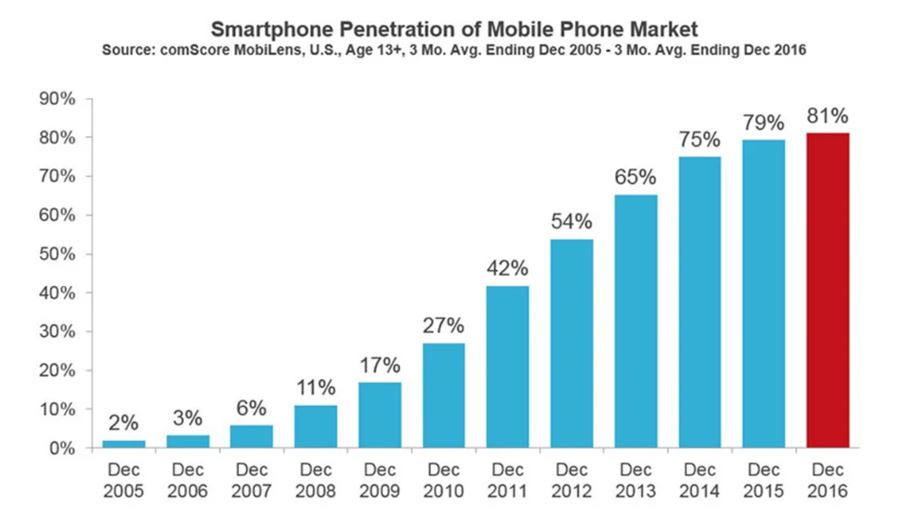

This begs the obvious question, “What is happening here?”. Jonathan Haidt’s theory – and I found his book very compelling – is that these massive declines in children’s well-being coincide with one equally dramatic change in the way that we bring up our children: the rise of the smartphone and social media. If you need convincing of that correlation, it’s time for another crazy graph, showing the rise in smartphone ownership between 2005 and 2016…

Basically, in 2011 less than half of the UK had a smartphone. Just ten years later 92% of UK mobile users had a smartphone. My eldest daughter was born in 2012, when if you were a kid and you wanted to look at a screen the chances are it was going to be a TV. Just eight years later my youngest was born into a world in which the majority of children will own a smartphone device which will fit in their pocket.

In seconds those smartphones can access basically any and every thing that other people can think to put onto a screen, the good, the bad and the really bad. It’s a device that the average person spends 3 hours and 15 minutes a day staring at. That’s the equivalent of about 50 days a year. I nearly threw up the first time I heard that statistic. The average person checks their phone 58 times a day. I’ve checked my own mobile phone usage stats on my phone and they made me want to cry. Whether you like them or not, over the last 15 years it seems indisputable that smartphones have changed our world completely. Don’t believe me, just look around you the next time you’re in a public place (NB you will have to look up from your phone to do this). Faces transfixed by screens, everywhere.

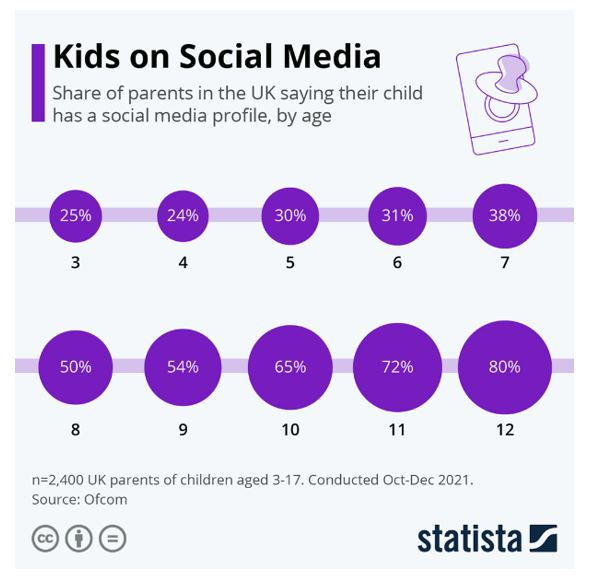

And if there’s anyone out there that still thinks that children aren’t being effected by this dramatic rise in smartphones and social media, another scary graph…

And as all of those graphs show, across almost exactly the same timespan that these devices and social media platforms crept into almost every aspect of our children’s lives (2010ish to 2015ish), those same children have become far more prone to depression, anxiety, self-harm and even suicide. And the tech use is still going up, and the mental health is still plummeting down.

Maybe it’s just a crazy coincidence. Maybe there’s some other explanation for this tidal wave of mental health issues in our children and young people. Or maybe – and this seems far more likely to me – the rise of smartphones and social media are two of the main culprits for the mental health crisis sweeping through our schools.

In Jonathan Haidt’s words: “It’s as though we sent Gen Z to grow up on Mars when we gave them smartphones in the early 2010s, in the largest uncontrolled experiment humanity has ever performed on its own children.”

So the headline news is this: SMARTPHONES AND SOCIAL MEDIA ARE HARMING OUR CHILDREN! But behind that main conclusion, there are lots of other aspects of this problem that are alarming.

There’s the fact that social media apps are designed to be addictive. I’ve only recently realised how significant this is. The more people use their apps, the more money the platforms make, so the addictiveness is not a glitch, it’s exactly what they’re aiming for. It’s how notifications, algorithms and infinite scroll work: they are literally designed to induce craving and make their products hard to put down.

There’s the impact on our children’s concentration (studies show that people literally perform worse in tests if they have their phone on the table, compared to if they are made to leave their phones outside the room).

There’s the data that shows that girls, LGBTQ adolescents, Black teens and those from low-income households are all more likely to experience harm from social media apps than those that aren’t from those groups.

And there’s the fact that research has long shown that negative emotions are more contagious than positive ones, so those affirming and positive influencers and social media posts are probably destined to be over-powered by the darker side of the online world.

Basically, it’s all very bad. My hunch is that most DSL’s are well aware that there’s a mental health crisis going on with our children. And they’re also acutely aware that social media use amongst children is common place and unhealthy. What the Anxious Generation book did for me, was to convince me that the link between these two things is very very strong, and that we won’t be able to solve the first problem without solving the second.

So, to come back to my original question: “Is anybody’s E-Safety curriculum actually working?”. On the evidence I see around me, not really.

Here’s where I think we’ve been going wrong (and by the way, by we, I don’t just mean DSL’s: I mean DSL’s, schools, politicians, parents and carers, all of us adults basically).

Firstly, we’ve placed too much emphasis on stranger danger online, and the risks of grooming and exploitation by adults. Just to be clear: these risks are real and we need to be teaching children how to avoid them. For entirely understandable reasons, we’ve been preoccupied with the risk of dangerous adults, who use the online world as a way to abuse children in the real world. But the consequence of this is that we’ve been so worried about our children meeting a sex offender on Omegle, that we haven’t paid enough attention to the impact of them spending a hundred hours a month on TikTok. It’s like we’ve been so busy teaching children not to smoke crack that we’ve missed out on the fact that they’re all smoking cigarettes. I am not sure if this focus has been effective in making children less susceptible to grooming or exploitation by adults online. But it’s obvious it hasn’t been effective in protecting them from all of the other more mundane and long-term ways in which smartphones and social media in particular can hurt our children.

The other way in which we’ve got our focus wrong is at the opposite end of the spectrum: we’ve been too pre-occupied with reducing general ‘screen-time’, without thinking enough about the different things that children do on screens, and what the different risks are for all of these different choices. Watching BBC iPlayer has about as much in common with watching Youtube as reading Michael Morpurgo has with reading Playboy magazine. These different on-screen activities have in common that they stop children from doing other things, like going to the park or playing with lego. But the similarities end there. The research on the harm done by general ‘screen time’ is very mixed and inconclusive. The research on the harm done by social media use on children is mounting and much more worrying.

And following on from these two major flaws in the way that we’ve been thinking about the risks of technology in our children’s lives, we’ve seriously miscalculated how we can keep our children safe online.

We seem to have decided that the answer is education. More education and better education. It feels like society has more or less bet the farm on this concept: enough E-Safety lessons in schools and we can teach the children how to stay safe in this brave new world. It’s an appealing idea. With the slight flaw that it doesn’t seem to be working. There is not a kid in my school – or yours I would wager – that does not know that you shouldn’t give out your address online. Some of them will still do it though. And some of the other ones will remember not to give their address to anyone, but will send them a graphic image instead. And most of them will do neither of these things, but they will follow hundreds of social media influencers on numerous platforms, consuming thousands of hours of content. And it seems like the cumulative effect of it all is quite likely to be worse mental health. In other words, even for kids who actually have managed to learn how to be ‘safe’ online, letting them use social media is still likely to make them much more sad, anxious or angry than they would be without it.

The online world is so huge and unregulated that no amount of education will prepare our children to navigate it safely. It’s like discovering that every child in Year 5 has got a bottle of vodka and a gun in their school bag, and your first response being: “We better get the class teacher to do some really good lessons with them on alcoholism and gun safety”.

I think we’ve gone down this road partly because there is some logic there. Someone needs to teach children about online safety and it’s a good thing that schools are trying to do that. Many of us have memories of ‘Just Say No to Drugs’ campaigns that seemed out-of-touch and ridiculous at the time, and the research shows were completely ineffective in the long-run. So instead we advocate raising children’s awareness and developing their own ability to keep themselves safe online. But I haven’t met a single DSL who’s told me that they think that their E-Safety curriculum is working. It’s not fair on schools and more importantly it’s not fair on children. They should not be expected to use the entire internet and all of the social media platforms out there safely: to spot all of the risks and always make the sensible choices. They’re kids: not technology experts with psychology degrees and monk-like levels of self-restraint. I for one am far from perfect now and was in many ways a complete idiot when I was a kid. I am very very grateful that I did not have a smartphone when I was 13 years old.

But I wonder if the other reason that society (everyone from politicians and parents to the NSPCC), seems to have settled on this approach is that it’s easy. In schools we have captive audiences and can deliver E-Safety lessons to our pupils whenever we want to, and afterwards we can say that we’ve done it. E-Safety has been covered in this school. Great, well done everyone.

But. It’s. Not. Working.

What we actually need to be doing is changing the laws around these things. Other countries are starting to do this and I really hope that one day we’ll look back and go “Do you remember when children used to all be on TikTok? That was crazy wasn’t it.”. But until then we need to change how parents and carers behave. They’re the ones who can really make a difference. And that’s a much harder job than delivering E-Safety lessons.

At the moment, when we do talk to parents and carers about online safety we jabber on about parental controls and app settings. Again, we need to be more realistic: the kids know more about this online world than we do. They know how to evade our controls and how to trick our weekly ‘checks’. If you are sitting next to your child and staring at the screen whilst they browse the internet then fair play, you are supervising them online. Anything short of that and you are not supervising them, you are at best keeping half an eye on them, and depending on how honest your kid is you are probably not even doing that very well. To all of those adults who are sure that that their kid is completely honest with them about their online life, ask yourself one question: How completely honest were you with your own parents when you were growing up about your crushes, sexual activity, forays into drinking, smoking or drugs and anything else that you thought that they might not approve of? There might be a small percentage of children for whom this monitoring and open discussion works. For a large majority though, it’s not the answer and only creates a false sense of security for us adults.

So where does all of this leave us then? With one blindingly obvious and very simple solution: take smartphones away from our children and keep them off social media. As Jonathan Haidt says, let’s make our norms and guidance simple, sensible and effective.

RULE 1

The accepted expectations should be that children should get a smartphone when they start secondary school, and not before then. Before that they can have a ‘feature phone’ if they need one for the school walk (£20ish on Amazon), and can use a laptop or computer in the living room if they want to use the internet.

RULE 2

Children should be allowed to use social media once they turn 16, but not before then. This definitely includes Snapchat but it also includes Tik-Tok and Youtube. The age limit of 13 that is set by the platforms themselves is not sufficient and not enforced. Social media as it stands is too powerful and too hazardous for 14 year olds to use it safely. Parents and carers are going to have to step in.

That’s it. That’s all the rules. Then E-Safety is about how we teach children to operate safely within that framework.

We’ve managed to get into such a distorted place that when I first read these two simple rules I thought they sounded ridiculous. But the more I thought about it, the more I realised that they are not a million miles away from my thinking for my own children, aged 12, 10 and 4. They got their smartphones in Year 5 and have had spells on Youtube - before we’ve got rid of it altogether because it was driving us mad - and apart from Whatsapp they’re not on social media at all. Yet because of my job I’ve become desensitised to really young children having smartphones and TikTok accounts, to the point where I’ve come to think that these things aren’t just normal, they’re inevitable.

But Jonathan Haidt’s book has given me the confidence to say what I honestly believe, as a parent and as a DSL. Even though I normally try very hard to avoid sounding like I’m giving other parents advice. The answer is staring us in the face: the easiest and best way to protect our children from the harms of smartphones and social media, is actually just to keep them off those things in the first place.

This might sound quite easy to some. But I accept it sounds like mission impossible for a DSL working with a whole school community and hundreds of different families.

For us DSL’s, it means we’re going to have to reach beyond our pupils, and speak directly to their parents and carers. We’re going to have to convince them of the case for making these changes. They’ll need a lot of determination if they’re going to try and force the genie back into the bottle. Because in some ways it’s going to make their own lives harder. If you’re a parent, trying to cook tea, clean up the latest spillage, fix the washing machine and occupy three children, then let’s not pretend that Youtube doesn’t have its advantages. And refusing to get your kid a smartphone, or let them go on Snapchat - when they’re telling you that all of their friends have it - is going to feel like you’re going against the whole world. You’re going to worry that you’re going to make your child an outcast, and you’re certainly not going to get any thanks from your little darling. But I think most parents and carers instinctively know that some of the technology is not good for their kids. I think a lot of those parents and carers already want to make these changes, and partly they just need us to cheer them on, unashamedly and relentlessly.

And that battle is going to have to be fought mainly in the primary schools, because if it’s a hard stance to maintain then it’s an almost impossible thing to reverse. But primary schools can’t do it on their own. We need as many people as possible to be pulling in this direction if we’re going to really move the dial.

I’ve rediscovered the dream of schools where none of the pupils are trying to work out how to get more followers, or watching damaging videos about self-harm, or sitting in their lessons unable to concentrate because they spent another night in bed doomscrolling until the early hours of the morning. And I’ve decided that the way to bring these schools to life is to get the politicians to change the laws or get the parents and carers to keep their kids off smartphones and social media. It’s that simple and it’s that complicated.

It will require time and effort, and conviction and creativity. And this is where I am now: at the start of a new journey. I really have not worked out the route yet, but I know where I want to get to. It's time to think outside the old box, and look for a new one. Let me give you one little example of what this might look like, taken from the Anxious Generation book: maybe we need to try bringing the parents of the children in Year 2 together, to unite them, and get them to pledge to collectively keep their children off social media?

We’re going to need ideas like that, and a willingness to try new things. I’d love to connect with anyone who is on the same path. Anyone who wants to keep our little people away from some of the worst aspects of modern technology, and let them just be children again. If you’re a DSL out there, and you feel the same, then do get in touch. Stood as I am, at the start of this journey, I want people to pose questions with me, share ideas and tell me about their successes and failures.

Picking up on my last blog piece, perhaps the first step towards making a real difference is to believe that we actually can. And I’m also sure that we will have a much better chance if we go together.