Are you looking out for the unknown unknowns?

In safeguarding we talk a lot about the differences between opinions, facts and speculation. But how else can we think about our knowledge: about what we know, and what we don't?

*NB This article contains references to families or children. The details in these descriptions are completely made up, but used to make relevant points and/or represent underlying truths that have come from real experiences I have had in my work.

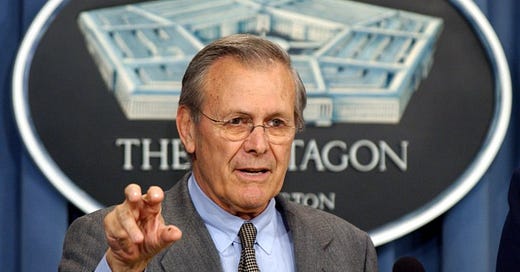

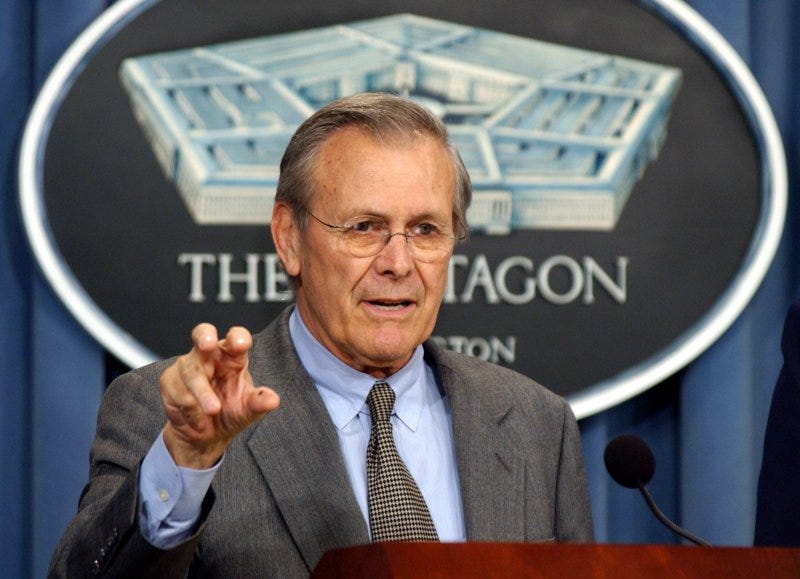

“Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know.”

Some of you might recognise this quote. It came from Donald Rumsfield – then the American Secretary of Defence - in February 2002. It was a time of tension and uncertainty, coming less than six months after the 9/11 attacks and just over a year before the Americans and their allies would launch the Iraq War. And Rumsfield was responding to questions about the strength of evidence linking the Iraqi government to terrorist organisations. And he was talking gibberish. Or was he?

On first hearing the quote, I thought he sounded senile. Or high. Or maybe both. Here was an example of a politician with frightening levels of power talking absolute nonsense: a jumbling ramble about how there’s things we know that are known unknowns?!?

But over time, the concepts that Rumsfield was fumbling with – if not the points he was trying to make with them – have come to have real value to me. By this I mean, I now really like the idea of known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns, and yes, I do actually find them useful as a DSL. Let me explain.

Basically, what Rumsfield was talking about were three different ways in which we can categorise our knowledge and our ignorance on any given issue. And I genuinely think that these different categories can be a useful way of thinking about safeguarding cases for DSL’s. But to make things simpler, I’m obviously going to expand his three categories into four. Prizes for anyone still reading at the end…

CATEGORY 1: KNOWN KNOWNS

Ok, these are the things that we know we know. Or more precisely, it’s the knowledge that we have, and that we realise that we have.

As DSL’s this is one of our most invaluable resources: our knowledge of the cases and families that we work with. It is the reason that in staff training we talk about record keeping and information sharing over and over and over again.

I doubt that there are any DSL’s who need convincing that collecting knowledge about children and families is a very important part of their job. But it is a means to an end, not the reason we are there. I have met professionals who seem obsessed with the idea of finding out everything they can about children and families, but then very limited in their ability to do things with that info. We shouldn’t fall into that trap.

Child protection info - like any knowledge - is only useful if you do something with it. Knowing about a parent’s drug addiction or about where a child stays at the weekend, is important. But it won’t solve all of your problems. Sometimes, when we are dealing with complicated situations and complicated people - even if we have all of the knowledge in the world - we are still left with the messy business of deciding how we were going to interpret things and what we’re going to do next. This is an obvious but easily forgotten reality.

With all of this in mind, the metaphor I would use for thinking about safeguarding information is not the often-used one of information being like a jigsaw (although I like that metaphor for it’s simplicity for non-specialist staff). I would suggest that for DSL’s, when it comes to accumulating information about the children and families we work with, we should think of ourselves more as museum curators than fossil collectors. We should be able to see that stockpiled information is useless if it’s just gathering dust on massive neglected electronic chronologies. Instead, just as in a good museum, the focus should not be on hoarding information, but on using it. On creating systems and habits that use our Known Knowns effectively: to really increase our understanding, so that we can make better decisions, so that we can take better actions, so that we can make our pupils’ lives better.

Key takeaway: The Known Knowns are great. But you have to decide how much time and effort you're going to spend finding things out, and how you're going to make sure that that knowledge is useful. Which takes us on to the next category…

CATEGORY 2: UNKNOWN KNOWNS

Now, to make things slightly easier, instead of ‘Unknown Knowns’, we can think of them as ‘Unrealised Knowns’. This is something that you have learned or known at some point (so you sort of know it), but then when it comes to the point where you really need to know it, you actually don't. In other words it’s knowledge that technically speaking you could have, but for some reason you haven’t realised: because that knowledge has been forgotten, misplaced or hidden.

To take an example plucked completely at random - that has absolutely nothing to do with my own personal life - if someone’s wife told them that they needed to remember to pick up some wrapping paper, but then they went to do the shop, forgot, came home without the wrapping paper, and when asked where the wrapping paper was, they said '“I didn’t know I needed to get wrapping paper”, then we could say that the problem they had was an Unknown Known.

For DSL’s, handling large amounts of information within large and complex organisations, this concept is critical. Because some unrealised knowledge is inevitable (obviously no one person can accumulate or recall a full and working history of everything that your organisation knows about a child and their family). But there are ways that you can reduce your unrealised knowns.

The first way you can reduce Unrealised Knowns is to make sure that you and your colleagues are sharing information well. If a DSL knows that Mum’s ex-partner was a risk to children, and a teacher knows that Mum’s ex-partner has moved back in, but no one knows both of those facts, then you’ve got a critical weakness in your system and a dangerous Unrealised Known.

Another way information can fall between the cracks is any time you record different types of information in different systems. So think about how and when you can transfer relevant info onto your safeguarding records (even if it’s just a note that says ‘attendance file opened’ or ‘big increase in behaviour incidents this term’).

But obviously the more you record and compile, the harder it will be to retain or access all of the information you hold. Here’s a Catch 22 that you also find with real life hoarders: they’re more likely than anyone else to have the thing you’re looking to borrow, but they're also less likely than anyone else to be able to find it and lend it to you.

It was thinking about chronologies that got me thinking about this whole topic (read my thoughts on chronologies here and find my tool for auditing them here), but here are a few other examples of things you can do to reduce your Unrealised Knowns:

- Specific DSL’s assigned to oversee big and long-term cases

- Flags or tags on online safeguarding systems, so certain things can be checked quickly

- Brief case summaries at key points (e.g. at the start of KS2, or when a Child Protection Plan is closing),

- Putting key details in CAPITAL LETTERS, so that they are easier to extract when browsing chronologies

Key takeaway: As you approach the end of the academic year, here’s my little exercise you can try to reduce Unknown Knowns in your school (it’s really for primary schools, but I’d guess you might be able to do an adapted version in other settings?):

Ask your class teachers to quickly rank every child in their class as Green, Amber or Red, from a safeguarding point of view

As a DSL, do the same thing yourself for each class (it actually works better if you do it really quickly)

Then compare your answers to theirs, and talk to them about any differences there are, to see where they come from

Then use this pooled knowledge to complete internal safeguarding handovers with new class teachers, at the start of the new academic year in September.

CATEGORY 3: KNOWN UNKNOWNS

These are the things that you realise that you don’t know. In safeguarding circles these are often called ‘grey areas’. They often come about when you’ve got a hunch, or some indicators that there might be an issue, but you’re not really sure of all the details.

For example, you’re pretty sure that a Mum is having real financial problems, but you don’t really know what the reasons are. You know that she hasn’t paid her dinner bill and that’s not like her, and that her phone has been cut off. But she doesn’t want to talk about her finances and maintains that everything’s fine. So whilst you want to believe her, you’re worried it’s all got something to do with the other things that staff have been noticing recently (a new partner, Mum maybe smelling of alcohol the other day and seeming very emotional at parent’s evening). So you’ve got a Known Unknown.

I think identifying Known Unknowns is really important, especially amongst professionals. They can be harder to discuss with families though, because sometimes the harder you root around for information, the harder it is to build trusting relationships with people. And if you’ve been given an explanation, but it still feels like a grey area to you and you want to keep exploring it, then it’s implicit that you don’t really believe what you’ve been told. You could ask Mum to see her bank statements, or ask one of her children why her phone isn’t working: those actions might help you to ‘get to the truth’, but they might get you no where or actually do more harm than good.

I guess the key here is to work out when to try and operate with a degree of unavoidable uncertainty, and when to set out to resolve some of your Known Unknowns in a deliberate manner, through direct actions you can take, rather than through never ending speculation. I’m really sorry to say that I have no simple advice on how to know when to pull those different levers though.

What I can say is that the longer I’ve been doing this, the more confident I am in asking adults questions directly when I think that there might be a Known Unknown lurking around (because I think that most people actually prefer that direct approach). And the more reluctant I have become to try and weadle information out of children (because I am very reluctant to put children who might have been told to lie to me, in the position where they have to lie to me). I’m not saying either of those things is ‘right’ though, just sharing my own perspective.

Key takeaway: People who abuse children can be evasive and dishonest. But so can people who are embarrassed, worried about being judged, lying on their benefits claims or scared that social workers are desperate to snatch their children. There is real value in understanding what is going on in a child’s life. But pursuing all Known Unknowns carries costs too. As DSL’s part of our job is to work out when to try and get to the facts, and when to be patient and keep an open mind.

CATEGORY 4: UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS

So these are the things that you haven’t even realised that you don’t know. And it was these that Donald Rumsfield was trying to draw attention to in the speech I started with. They’re the things that you haven’t even been speculating about, so when you discover them they really do knock you sideways. The time that you learn that the older sister has got a serious drug addiction, and your jaw hits the floor because it had never occurred to you that she might have. When you’re not wondering what the new boyfriend is like because you don’t even know he exists. Or you discover that the child who has been quietly getting on with things and acting completely ‘normally’, has actually been single-handedly looking after three siblings for the last two months.

And when we’re suddenly confronted with an Unknown Unknown, we’re reminded about just how many Unknown Unknowns there are in the lives of our pupils. One thing you can probably be sure of, is for all of the knowledge that you do have, it is a drop in the ocean compared to all of the knowledge that you don’t have.

Think about it this way: imagine if tonight the entire actual safeguarding history of all of your children was going to be loaded onto your safeguarding system. So that in the morning every single chronology wouldn’t just contain all of the things that staff have previously recorded, but would contain every single thing with any safeguarding relevance that has ever actually happened in the lives of all of your pupils. The mind boggles at how much reading you’d have to do, and at how many previously Unknown Unknowns you’d have to discover. You couldn’t predict exactly what all of the surprises would be, but you know that there would be lots of them. That thought experiment just reinforces the importance of staying humble about your level of knowledge in the safeguarding arena.

Apparently when they build new nuclear power plants they have a ‘What If’ brigade that sit around trying to think about Unknown Unknowns: to come up with unforeseen scenarios that might present a risk. What if someone brought a firework into the office, and then inadvertently set it off, and then it blew up the control panel? How do we prevent that from happening, and what’s the plan if it does?

Now I’m not necessarily suggesting that you do this particular exercise, or become a paranoid android. And I mean, if you can’t set off a few fireworks with the Year 4’s on a Tuesday morning then what’s the point in being teacher? [Obviously that’s a joke. Setting off fireworks is much more of a Friday afternoon activity]. But it is a good idea to be mindful of Unknown Unknowns, and to sometimes ask yourself what they might be. I think we can do this with individual cases: e.g. ‘What might really not have occurred to us that could explain this child’s behaviour?’ And I think we can do this with our safeguarding systems: e.g. ‘If safeguarding really failed in this school, in a way that took us by surprise, where might that failure come from?’

Key takeaway: Remember, as Socrates almost said: the smartest DSL is the one who realises just how little they really know.

Well done to anyone who made it to the end, I promise next week will be less rambly. Probably.